Rensselaerville Hamlet History

|

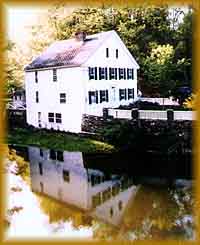

Rensselaerville township is composed of the hamlets of Rensselaerville, Medusa, Preston Hollow, Potter Hollow, and Cooksburg in the southwest corner of Albany County, New York. Owned from 1629 by the Dutch patroons Van Rensselaer and part of the huge Manor of Rensselaerwyck, the area was so inaccessible that it was not settled until the late 1700's. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, Stephen Van Rensselaer III advertised "free" tracts of land of 160 acres to anyone who would develop the land. After seven years, farmers had to pay an annual rent of four fat fowls, 18 bushels of wheat and a day's service. The rents were perpetual and binding on subsequent purchasers of the land and the patroon reserved mineral and water rights. These "incomplete sales" led to the Anti-Rent Rebellion 1839-1889, which influenced the wording of the Federal Homestead Act of 1862 and opened up the west to settlement. Many war veterans took advantage of Van Rensselaer's offer, coming mostly from Massachusetts, Connecticut and eastern Long Island by boat up the Hudson River. By the 1787 Cockburn survey, there were a few houses scattered throughout the township, but none at the future site of Rensselaerville hamlet. Two miles southwest, however, at "Mount Pisgah" (now "Kropp's Hill") was a small settlement and the first Presbyterian church services were held in a log cabin there in 1792. For nearly a hundred years thereafter, the township thrived, with dense forests of hemlock providing bark used for tanning leather and abundant water power making milling of lumber, grain and wool important industries for many years. The local grist mills and ready markets helped support a robust agricultural community in the surrounding countryside. By the mid-1800's, however, the forest resources began to dwindle and

rail and water transportation for goods bypassed the hamlet. Industry

moved closer to less expensive means of transportation and mechanized

farming techniques proved more efficient on large, flat expanses of

land. Further, as forests were cut, the land lost its ability to retain

rainfall, causing a severe drop in the watershed. One by one, the water-dependent

mills went out of business. As others left our rocky hills for better

opportunities in the newly-opened west, a few hardy farmers stayed on.

Today, Rensselaerville is mostly residential, with an interesting blend

of retirees, young professionals, and descendants of early settlers.

Much stunning 18th century architecture remains, tastefully adapted

for contemporary use, and agriculture remains essential to the character

of the town. Explore the rest of Rensselaerville.com to discover other

ways in which our town combines the best of the 19th and soon-to-be

21st centuries!

|